Many people in Singapore are underwhelmed by the news of war in Ukraine. Apathy is one obvious reason, but it is not the only one. We know Singaporeans who care about world affairs, but are resisting emotional investment on the side of the victims of the conflict, which they see as a spectacular display of Western double standards.

Some recoil at the sight of the United States trying to whip up moral outrage at the Russian invasion of Ukraine, when Americans themselves have not been held accountable for decades of abuse of its superpower status. The sharper American and European official rhetoric gets and the more hyperbolic the media coverage from these places, the deeper these Singaporeans’ sense of injustice — not at Vladimir Putin’s unhinged assault on the Ukrainian people, but at Western hypocrisy.

The opinions of citizens of small distant nations like ours have little bearing on events in Ukraine, and that is not the reason why we think it is worth examining this particular point of view. We see the shockwaves from Ukraine as a kind of stress test — not currently consequential, but potentially problematic when stakes get much higher. Responses to the war in Ukraine suggest that Singaporeans may be vulnerable to ways of thinking that may cloud our judgment when geopolitical crises emerge closer to home.

Often, a piece of news about the war instantly triggers much wider debates over the relative merits of whole nations and civilisations. Ukraine has thus become a theatre in larger identity wars, an occasion to score points for one’s team or deduct points from the other. Many are so psyched up for this contest that they suppress their genetically inherited capacity to care about fellow human beings, lest images of corpses and refugees soften their resolve to serve as ideological foot soldiers for their chosen side.

We share people’s scepticism when a US president claims moral leadership in international relations. But, that is no reason to discard our own moral compass — which is effectively what we’d be doing if we harden our hearts to the humanitarian cost of Russia’s behaviour. Decolonising our worldviews requires us to see events independently of where big powers stand. To fail to do the right thing because it happens to coincide with what the US wants is not a mark of a self-assured society. It is a form of overly simplistic, dispositional thinking — in this case, “US, bad; anything non-US or anti-US, good” — unsuited to life in a complex world.

Abuses of US hegemony

Since World War 2, Singapore has largely benefited from the US’s role as “the world’s policeman” and the chief underwriter of the global economy. The US forward military presence in Asia, its general support for economic liberalisation, and broad acceptance of international legal norms has helped create a space for Singapore to prosper economically. Not all countries have been so fortunate. In some parts of the world, American policing has been felt like an unremitting knee on the neck. The US has engaged in direct military actions in violation of smaller states’ territorial integrity, persisted with “surgical” drone strikes despite mounting civilian fatalities, helped subvert people’s democratic will in US-backed regimes, and supported allies’ illegal occupation and subjugation of nations struggling for self-determination.

US Secretary of State Colin Powell’s infamous performance at the UN Security Council on 5 February 2003, holding a model vial of anthrax while making the fraudulent case that Iraq was building weapons of mass destruction. Wikipedia Commons

Majority-Muslim regions of South and West Asia as well as North Africa are especially famiiar with the dark side of American intervention. Even after the colonial era, the US and its allies interfered regularly in the domestic politics of Muslim lands, helping to engineer coups and propping up authoritarian regimes. In 2003, the US justified its invasion of Iraq on the basis that Saddam Hussein was readying weapons of mass destruction — a claim no more truthful than Vladimir Putin’s excuses for invading Ukraine. The George W. Bush administration brushed aside objections from the United Nations Secretary-General, Kofi Annan, who said the attack was illegal. Even US allies Germany and France refused to go along with Washington’s plans, much to the chagrin of US politicians. In addition to killing hundreds of thousands of people, this exercise in “regime change” contributed to further destabilisation of the Middle East and the rise of the Islamic State terror network.

Especially painful for many Singaporeans to watch is the plight of Palestine. The US has on multiple occasions vetoed or voted against UN resolutions in favour of the Palestinian people and statehood. In 2020, it was only one of five countries that voted down a resolution to recognise Palestinian statehood and end Israel’s occupation, while 163 countries voted in favour.

Double standards are found in Singapore as well. Public expressions of support are more welcome for some victims of aggression than others. When Singaporeans, especially Muslims, see how openly our fellow citizens are able to advertise their support for Ukraine, they cannot help but recall how they are prevented from showing solidarity with Palestine. Street artists, for example, have found their pro-Palestinian symbols censored even when painted on spaces legally allocated for graffiti. Thus, censorship in Singapore brings the unfairness of the US-led global order home. The Singapore government is not unsympathetic to the Palestinian cause: it has sided with the majority of states in UN resolutions and recently contributed healthcare assistance to Palestinians, for example. Nevertheless, there is a stark contrast in the tone of establishment reactions to the traumas inflicted on Ukraine and Palestine.

Israeli soldiers patrol an open-air market in Hebron. Wikipedia Commons

It is no wonder that people cringe when the US and its allies talk about having to restore the pre-invasion global order. To many people in China — and, evidently, some among the Chinese diaspora in Singapore as well — what the West calls order is really a hierarchy, a global caste system designed to keep a rising Asian power in its place. Even when taking at face value US calls for the integration of China as a “responsible stakeholder” in global order, such rhetoric suggests that China needs to conform with rules and structures created by the US, largely to benefit US preeminence. Meanwhile in the Global South, the US-backed status quo has meant uneven responses to humanitarian crises, partly for geostrategic reasons and partly because global white privilege means that the suffering of peoples of colour are not taken as seriously. For post-colonial societies especially, Joe Biden’s bid to rally international support against Russia pushes the wrong buttons.

Two wrongs don’t make a right

Therefore, when US opinion leaders talk about the Ukraine war as a “contest between democracy and autocracy, between sovereignty and subjugation”, as President Joe Biden put it, it is reasonable to doubt their sincerity and consistency. Where we part company with this critique, though, is when it loses sight of the desperate urgency of Ukrainians’ plight, and ignores the fact that they should have a say in their own future. We also find it alarming that there are even members of the establishment and other educated elites who readily propound untruths without any apparent efforts at corroborating claims — such as the debunked conspiracy theory about US-funded Ukrainian bioweapons facilities. The overriding motivation when processing and sharing news and information seems to be to win one for the team against Western adversaries.

Such eye-for-an-eye reactions threaten to leave Singapore morally blind. It need not be this way. One can most definitely do two things at once: criticise American aggression and hypocrisy, yet at the same time condemn Russia’s invasion. In fact, that is the most reasonable thing to do. Most of the time, big powers try to get away with foisting their preferences on others. It is up to the rest of the world to hold them to standards that conform to international law and morality. As a small country, Singaporeans should be more acutely aware than most about the excesses of great power politics, regardless of which happens to be the offending big power in a given crisis.

The universal human rights enshrined in the UN Charter are among the standards we should insist on — instead of surrendering to the common but erroneous perception in Singapore that these are a “Western construct” driven by “Western” people and their ideas. To avoid the hypocrisy we accuse others of, we should of course be prepared to be held to the same standards we expect of big powers. We are hardly paragons of virtue in our global outlook. For example, pro-China Singaporeans have been quite silent about the plight of brown Muslims in Kashmir and brown victims of military-led violence in Myanmar — including the mass atrocity against Rohingya. A human rights lens can help correct Singaporeans’ own ethnic prejudices as we demand a fairer and more just global order. Our goal should not be to tear down one set of ethnocentric double standards only to replace it with another.

East Asians have not been vocal about the rights of Rohingya refugees, raising questions about their own ethnocentricism. Rohingyas at the Kutupalong refugee camp in Bangladesh, October 2017. Wikipedia Commons

It is normal for wars to activate national, ethnic, and religious identities. But, we can choose whether to give in to those instincts. We do not need to regard the war in Ukraine as a civilisational conflict between the West and the Rest, even if that is how others choose to frame it.

If, as many have observed, Singaporeans are less pro-Russia than they are anti-US, we should consider what good such US-centricity does us or the world. Putting the US front and centre elevates it to the “city on a hill” that many in the US like to think of themselves — the key point of reference against which to measure our fears and hopes. It need not be. If we care about justice, we should focus instead on figuring out what behaviours are acceptable or not, regardless of who engages in them. Abhorrent actions need to be called out and criticised, whether this is Russia supporting the Assad regime’s use of chemical weapons on civilians, or the US using the toxic chemical defoliant Agent Orange in Vietnam. Alleged Russian efforts to replace the current Ukrainian government led by Volodymyr Zelenskyy with a puppet regime is at least as bad as the American roles in toppling popularly elected leaders like Salvador Allende and Mohammad Mossadegh.

Beyond Ukraine: Implications for the future

The way Singaporeans respond to events 5,000 miles away matters because we can expect similar tests of loyalty and conscience closer to home. The Ukrainian crisis will unfortunately not be the last time when the pulls of identity are entwined with geopolitics. Already, we have seen how various communities in Singapore respond in different ways to the rise of China — just as they have to events in the Middle East. The government is clearly worried about insidious Chinese propaganda manipulating public opinion, even if officials (other than retired diplomat Bilahari Kausikan) have been coy about naming the threat, sometimes even referring to decades-old examples and recycling familiar anti-liberal tropes in order to avoid the current elephant in the room.

It is no accident that Chinese propaganda has resonated among many Singaporeans. Analysts of both Chinese and Russian propaganda over the past several years tell us that these states have latched onto a strategy of exploiting latent anti-Western (and, in the West, anti-establishment) sentiment in publics around the world.

Historians would tell us that this is hardly a new strategy for rising powers. Imperial Japan disseminated anti-colonial propaganda throughout Asia to persuade subjugated Asians to support “liberation” under a Japanese-led “co-prosperity sphere”. Contemporary Chinese propaganda and outreach efforts, in particular, aim to activate the loyalties of ethnic Han communities around the world and tie them to the interests of the PRC state. Segments of the ethnic Chinese population in Singapore, with our less developed sense of national identity, may be more susceptible to such persuasion.

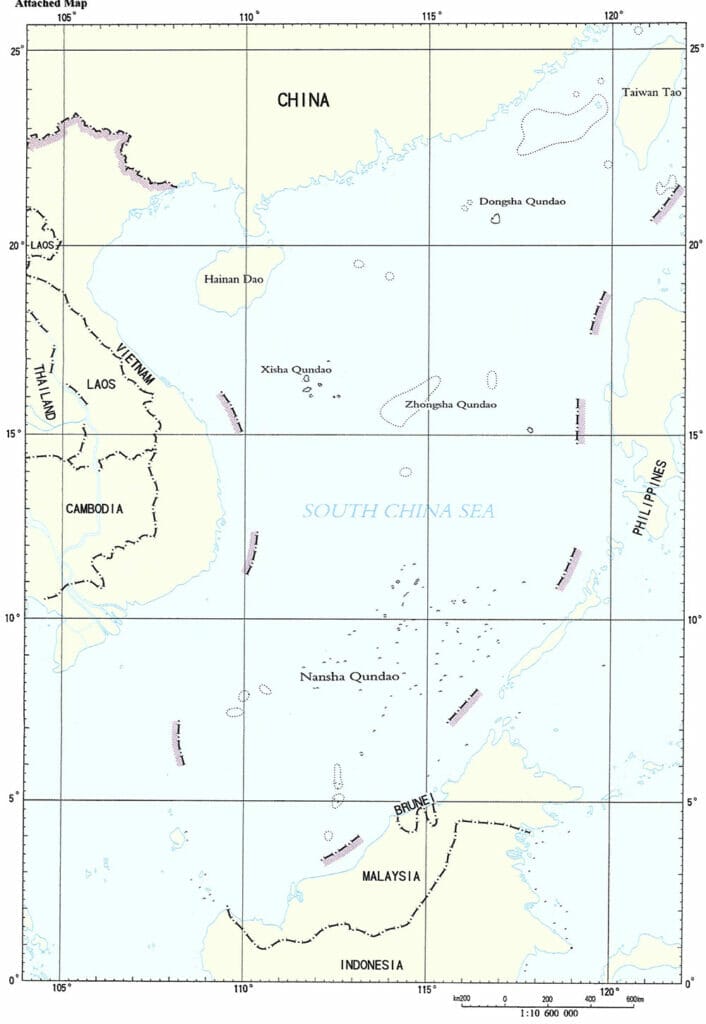

China’s 2009 nine-dash line map submission to the UN. Wikipedia Commons

China today does not have the same territorial ambitions of Japan a century ago. But the misbehaviour of the People’s Republic, even after discounting Western hype, should not be overlooked. China’s construction of military bases on disputed South China Sea islands shows no respect for its Southeast Asian neighbours. Within the country, its treatment of Muslim Uyghurs in Xinjiang does not (contrary to US rhetoric) reach the legal threshold of genocide, but its forced mass “re-education” certainly amounts to “collective repression” of religious and ethnic minorities. This calls into question whether the contemporary Chinese state will have the multicultural sensibility to deal sensitively with its bewilderingly diverse Asian neighbours.

Singapore state and society need to be able to discuss such issues in a studied and sober manner. It will not help us if, instead, every discussion about the conduct of foreign powers degenerates into a pointless parlour game of who’s better and who’s worse, or as the Chinese phrase goes, “compare rottenness” (比爛 bǐ làn). This “whataboutism” is exactly what we observe in many conversations about Ukraine. Getting sucked into endless debates about whether the US is better or worse than its rivals impedes reasonable thinking, because it does not allow any situation to be assessed on its own merits. Agreeing with the US on supporting Ukraine against Russia need not mean support for the US on the Israel-Palestine issue. And, wherever the US stands in our esteem relative to other giants should not determine Singaporeans’ own position on its policies.

The trap of identity politics

This obsession with sides, identity, and dispositions will desensitise Singaporeans to the faults of whatever side we choose to identify with, while underestimating the interests we share with others. Much more is at stake than proclaiming yourself to be a diehard fan of one English Premier League club or another. We need a more intelligent understanding of international politics and history, to recognise that big powers, for all their rhetoric, will always try to shape and game the system to their advantage — but, equally, that it is counterproductive to limit our choices by unnecessarily demonising them.

When Singaporeans refuse to share the West’s alarm at the Ukraine invasion, this may be a natural reflex of people trying to resist Western domination. It is not, however, the mark of a decolonised mind. Americans and citizens of self-confident nations do not bother to ask themselves if their viewpoints are too Singaporean, for example. A mature Singaporean public, similarly, should not decide what principles they embrace based on where others stand.

Nor is the answer to stake a position equidistant from opposing sides. That sort of unreflective neutrality is consistent with the “kiasi” inclination to keep one’s head down and to avoid trouble. From this perspective, the principles and interests being contested matter less than emerging intact, or better yet, coming out ahead. This appears to be what many Singaporeans mean when they say the country should “not choose sides” among the great powers of the world. It ignores the fact that major powers can act arbitrarily and there may be times when hiding from the wrath of stronger actors is not possible.

Instead of a neutrality that borders on disinterest and indifference, Singaporeans may be better served by striving for impartiality — making the best decisions for ourselves without fear or favour, to create options for Singapore rather than to keep fretting about some artificial and simplistic “China or the US” binary. Those two giants do not need Singaporeans’ help defending their honour. Nor are Ukrainians hanging onto Singaporeans’ every word as if their lives depended on it.

Our time is better spent appreciating what is at stake in the longer term for a smaller actor situated in an increasingly contentious part of the world, and finding ways to defend its position. One of these is standing with international norms designed to protect weaker and less privileged actors as a first line of defence, regardless of who the aggressors are. After all, if Singapore gives up on the right of weaker actors to not be invaded by stronger ones or to defend themselves, including by securing external partners, this will help usher in global norms that are more threatening to Singapore’s interest and, indeed, survival.

Government leaders and other establishment opinion makers have in the past been quite frank about external threats, even at the risk of upsetting segments of the population. From the time of independence, they have highlighted the risks of foreign interference. In more recent decades, they have openly pinpointed Islam as dividing Muslim Singaporeans’ loyalties, and warned about the influence of exclusivist and intolerant strains emanating from Saudi Arabia. Such efforts can overstate dangers and fuel unnecessary suspicions.

But, when done responsibly and sensitively, such conversations and debates help Singaporeans see that their multiple identities are not inherently incompatible — one can, for example, be a more devout Muslim and a more patriotic Singaporean at the same time. Perhaps it is time for similarly open conversations with Singaporeans who feel the pull of China. Such organic discussions, even if sharp at times, can be especially productive if they foster a clearer sense of common civic values undergirding citizenship in Singapore — values that we can hold one another as well as those in authority to. They are likely to provide more protection against disinformation and propaganda than what government-led labelling efforts can offer.

The temptation to see the world through big power lenses is strong, and is actively promoted by influencers and state-affiliated entities with far more resources than we in Singapore possess. But they will not succeed if we as citizens decide not to play that game, and to instead be guided by facts, conscience, and a commitment to peaceful co-existence.

Cherian George, Chong Ja Ian and Jumblatt Abdullah

Cherian George is a media studies professor at Hong Kong Baptist University, studying disinformation and hate propaganda. Chong Ja Ian, a political scientist at the National University of Singapore, researches international security and Chinese foreign policy. Political scientist Walid Jumblatt Abdullah of Nanyang Technological University specialises in Singapore politics and state-Islam relations.

This article is republished, with thanks, from Academia SG

Banner image: Daniele Franchi, Unsplash